popol maya

According to its introduction, popol maya is “not just a game” but a belief system. Supposedly, its tenets are based on Maya mythology, though it flagrantly misinterprets everything about that culture save for a vaguely tropical setting. The game stumbles onto its own ideas instead, attempting to solve that universal question of how to find meaning in a disorderly, malevolent world.

The game settles on communication. We need to listen to each other. popol maya wraps its answer under layers of groaning animals and dancing, and somewhere along the line, it forgets to link its spiritual dilemma more closely to the bizarre happenings at hand. The message comes through from the whole of your Maya adventure, but it might have shone stronger if – ironically for the theme – the game spoke to you more.

In the popol maya mythology, the world is governed by the “universal principle.” It’s an energy that binds life and time together, born from “chaos and contradiction.” The game means to connect you with that energy. You are reborn as an avatar, a golden, sun-headed stick figure, sent to find the “trick animals,” ancient souls who reveal the universal principle “just as the windmill shows us the presence of invisible air.” With their knowledge, you will become Maya… or whatever the game’s version of Maya is. (For the rest of this article, assume that “Maya” never refers to the real civilization.)

popol maya lays all this out in a erratically translated wall of text. It’s basically a lot of gibberish. The concepts are a bit clearer in practice (it makes a better game than a pamphlet).

popol maya‘s intense imagery, like these underwater cliffs in AQUA, feels half-remembered even in the moment

The Maya world has three planes, standing for the earth’s surface, water, and underground. popol maya presents these settings as vivid, looping panoramas. Short clips of undulating electric piano music guide you through canyons and forests, where the background details blend together. The impression is less of a color or mood than a texture. I can barely recall separate sections of SUBTERRANEAN, the underground, but I remember its cragginess and a rough haze that looked like a charcoal rubbing.

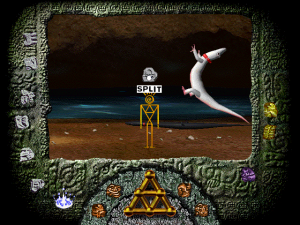

Across this world, your avatar meets trick animals, like a screaming cow featured on the game’s box. popol maya twists familiar animals in odd directions, like a giraffe that scuttles around like a crab, fish that change their patterns to show their moods, or a pair of sentient scallions. Some of these animals will hurt or deceive you; if you hit the cow, it will sit on you and crush you. Most others don’t really care about you that much.

Your goal is to understand the animals by resisting their tricks, helping them out, or just paying them some attention. You interact with everything in popol maya by typing verbs. When you run into an enraged rhino-like beast, you need to “dodge” it. Solutions could be as simple and natural as “touch”-ing a snail and watching it stretch out of its shell. The game has dozens of verbs to teach animals or to learn from them, including a few without a practical purpose. (What other game lets you “perceive” something?)

When you solve an encounter with a trick animal, your avatar learns a dance. This is the language of the universal principle. Every dance, coded with a letter or number, is a single unit of understanding, condensed from your experiences. Even a non-sequitur encounter, like putting together two rats and getting their eyes to glow, brings you more in touch with how the Maya world moves.

As the old popol maya website explains, this is animism, the idea that everything in the world has life and can be listened to. Yet the game doesn’t suggest what, really, you’re hearing from them.

Despite being about communication, popol maya continually omits crucial information. Discovering how a game ticks can be a great joy, and although popol maya provides plenty of opportunities to figure out its rules for yourself, it strands you without the vocabulary to do that. Sometimes that vocabulary is literal: the game doesn’t tell you any of its verbs. The open prompt builds excitement to think up new ways to interact with the animals… until the game wants you to “overturn” a turtle rather than “flip” it. Or to “recover” from an injury before the game teaches that. Or to “move” to gain the ability to walk around at all. Even once you know the words, you get poor assistance about how to use them. One scene requires you to “strike” a frog in a particular spot, and in the absence of feedback from striking the frog anywhere else, you’d probably assume you need a different verb instead.

popol maya keeps following this pattern – broad possibilities missing the steps to specific actions. The Maya world is a twisty labyrinth, perfect for drawing maps and identifying landmarks, but the game hides some of its paths behind unmarked surfaces or wide open spaces with no visible patterns or clues.

More than any mechanic or structural miscommunication, popol maya struggles to extend meaning from your interactions with trick animals to the dances you carry from them.

The game implies that each animal has a lesson or meaning to impart, but the dances you learn have no distinct qualities. Their motions are elaborate – your Maya avatar is one of the more expressive and energetic characters in memory – but they have no relation to where they came from. Suppose you encounter a family of squirrels and befriend them by sharing nuts; nothing about the dance you learn calls back to the camaraderie of that experience. Once you accumulate four or five dances with generic letters or numbers for names, they’re indistinguishable.

The dissociation seems to be intentional. As you learn dances, the game adds their letters to your “maya-name,” a long nonsensical title meant to summarize your life. Threaded together like this, the dances lose their individual meaning; instead, collectively, they express how you’ve grown as you’ve listened the world. It embodies the big picture of your experiences. That would be fine if popol maya didn’t still ascribe the dances their own values.

The dances aren’t just symbols. You use them, too, to pass through the Maya world. Giant monsters block the passages between planes, and when you speak to the monsters in the universal dance language, they will drop their guard, show their true selves, and let you through. One road out of SUBTERRANEAN is blocked by a bulbous root creature; if you dance for it correctly, it will spin and slowly reveal, under its dirty exterior, a globe.

Bonding with the monsters like this attests to the beauty of connecting with another living creature, the core of the Maya philosophy. But these confrontations – the game’s climactic puzzles – want you to direct specific dances to specific spots on the screen in the right order. Why those dances? Why those points? You’re speaking phrases from a new language phonetically. You’re carrying on a conversation despite not understanding the words. Without knowing what the dances mean and when or where to perform them, you’re basically randomly dragging dance icons around the screen until the monsters open up. That’s not communication or even a puzzle. It’s just guessing.

(Coupled with how very slowly your avatar walks, this game demands deep patience.)

Still, at times, the universal principle informs an entire scene, and those moments conjure up the profound metaphysical comfort that popol maya promises in its opening. In the jungle plane TERRAFIRMA, I found a bear resting in a hollow tree. I told my avatar to “sleep” next to it. The music stopped. When my avatar woke up, the sun had set outside, and I learned a dance from our time together. The whole exchange lasted less than a minute, the action was intuitive, and it brought me closer to how one animal lives in harmony with this world. It was almost like playacting or performing a role in a fable. And it was pretty darn charming. I took a nap with a bear!

Not much else in popol maya speaks so directly, and the game is trapped between seeming meaningful and articulating that meaning.

In popol maya‘s finale, your avatar travels to the fourth Maya plane, MACROCOSM, where it meets a huge oyster floating in the center of the universe. You perform your dances one final time, and it transforms your dances into pearls, placed on a part of your inventory unused until now. Then your avatar boards the oyster and sails off into the unknown.

It feels cathartic. You’ve grown closer to the animals and the pulse of the Maya world. Now that closeness has turned into a tangible thing. As with your maya-name, the game looks at your journey in the abstract and ties a bow on the overall arc of your story.

It also ignores the experiences that brought you there. The dances lost their own meanings much earlier; the ending is so far removed from the original reasons the dances mattered that the trick animals may as well come from a different game. Which pearl represents that time I took a nap with a bear?

Contrast this with the ending to another philosophical adventure game, Eastern Mind: The Lost Souls of Tong-Nou. Eastern Mind also culminates with a symbolic destruction of your adventure – sacrificing a collection of glyphs and tokens to retrieve your soul. Unlike popol maya, the items in Eastern Mind invoke the names of your past lives and the themes of the setting, and the final room is circled by statues of characters you’ve met. You never forget where you came from, and it gives satisfying, contextualizing power to the game’s last moments.

The problem seems to be that developer Shadow Entertainment offloaded the game’s thematic resolution to a website that, of course, no longer exists. When you complete popol maya, you’re given a URL where you could learn “the secrets of your maya-name.” We’ll unfortunately never know what, if anything, the site said. Without that, the sum of your Maya life is a contextless jumble of letters. And so the game ends basically unfinished.

popol maya can’t decide whether your individual actions matter or just their combined value. We might never be sure. Once again, the game has trouble sharing specific details out of its vision.

So what if the trick animals ended up being mostly nonsense? The game wants you to listen to them. Becoming Maya isn’t following a list of morals. It’s about opening yourself to how others live. popol maya shares that message over and over to its end, though with noticeable gaps between what you do and how you get there.

Trivia!

Completing the game leads to an alternate playthrough with new animals. It ends the same way by pointing you to a different maya-name website, which also no longer exists.

Download

In the interest of preservation, I have uploaded popol maya to the Internet Archive. Big thanks to Tumblr user compudsgn for ripping and scanning the game and sharing it with me! The Internet Archive download includes MAYASEL, a fan-made tool by A. Shimada that allows you to play with more than one save file.

I realized I hadn’t linked to this anywhere, so for posterity, here’s a link to the only guide to popol maya currently. There’s some issues running it through Google Translate, but it was very useful for getting an idea about what to do next: http://shimada.my.coocan.jp/game/popo1.htm

What was the URL at the end?